The controversy over the decision by the board of directors of San Francisco Pride to revoke their selection of Private First Class Bradley Manning as a grand marshal for the 2013 parade has highlighted what most queer San Franciscans have long recognized: SF Pride is a soulless endeavor beholden to corporate capitalist interests and directed by a handful of career professionals who value the comforts of assimilation over confrontational politics. Nor should the dysfunction and incompetence signaled by the way the board of directors has handled the controversy surprise any serious observers of SF Pride, who have watched the organization stumble repeatedly in the past several years. A city controller’s report of SF Pride’s bungled finances exposed the extent of the incompetence in 2010, and a series of poorly timed resignations revealed persisting difficulties well into 2011, even prompting the illustrious Michael Petrelis, never shy to speak truth to power, to advocate canceling Pride’s events that year, and dissolving its board altogether.

Certainly, now more than ever, SF Pride requires public scrutiny, and if its legally bound directors refuse to operate transparently, the community must take action to replace them. A diverse group of writers and activists, from locals like Petrelis, Glenn Greenwald, and Clinton Fein, to the far-flung like Victoria Brownworth and Jesse Monteagudo, are on the case, and one can expect the pressure on SF Pride only to build until the directors answer the community’s concerns; the recent announcement by SF Pride to postpone any opportunity to do so until after the June 30th celebrations is thus all the more puzzling to anyone familiar with the rudiments of community relations. The incompetence continues.

Whatever criticism observers may rightly reserve for SF Pride, though, I am equally troubled by the failure of another player in this drama. Those active duty members and veterans of the military who demanded SF Pride take the ill-advised decision to rescind Manning’s selection not only demonstrated their utter ignorance of community relations, they also showed both a deep disrespect for a convention of martial culture essential to maintaining civilian democratic authority over the military – the legal duty of every soldier, sailor, and marine to refuse to obey unlawful orders, and to report others who violate military or civilian law – and a regrettable disregard for the free, pluralistic society one’s military service is intended to secure. While I can easily overlook their naiveté of public affairs, their disrespect for the legal complexities of Manning’s case, and their disregard for pluralism impress me as dangerous indeed.

Advancing the first criticism is challenging for a self-professed anarchist like me, as it relies on legal paradigms I do not myself accept as valid, but those legal paradigms nonetheless operate as the framework for construing concepts of military duty and obligation, and function as the sole constraints on the exercise of military power by the democratic state, civilian authorities, the chain of command, and the troops themselves. So, peaceful society relies on these legal paradigms to avoid the perils of military force run amok. The sworn duty of every inductee into the armed forces is to obey all lawful orders, and much of military training is structured to teach every member to do so without question, but the obverse of that Janus coin is the duty to refuse unlawful orders, and instruction in the Uniformed Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) is meant to teach every trainee to be able to discern the difference. Manning was clearly paying attention in class.

As for Manning’s critics among the queer military community, I’m not so sure. The contempt these supposedly upright service members hold for the complexities of law is apparent even in the short quotes they’ve provided to the media: all have spoken of Manning as if he had already been convicted, which he certainly has not, and prosecution on the capital crime of aiding the enemy is highly improbable according to some legal observers, who say the government is overplaying its hand. Stephen Peters, president of the American Military Partners Association, called Manning’s alleged acts “treacherous,” and accused him of “blatant disregard for the safety of our service members and the security of our nation.” Josh Seefried, co-chair of OutServe-SLDN, an organization one might have thought should have supported Manning, called Manning’s alleged acts a “disgrace.” Navy veteran Sean Sala even asserted that Manning “makes Gay military, the Armed Forces, and the cause of equality look like a sham.”

I’m unsure how these critics have arrived at their conclusions. Other critics have referred to Manning’s “confession,” by which, I presume, they mean his statement before the providence inquiry in February. I have lately suspected the most voluble opponents of Manning’s selection as grand marshal have perhaps never read that statement, because Manning was eloquent in the defense of his actions, especially eloquent to anyone who ever served. Service members and veterans should know, better than civilians and non-veterans, that the induction oath sworn by enlistees and commissioned officers and the UCMJ, in which all service members are well indoctrinated and of which ignorance among the troops is not tolerated, require that service members refuse unlawful orders. Under Article 81 of the UCMJ, prohibiting conspiracy, therefore, no authority can require a service member to conceal the violation of other laws. In other words, once Manning knew that others were breaking laws or ignoring the military’s own rules of engagement, he was duty-bound to come forward, and if the chain of command were complicit in said violations, he was duty-bound to find another way to blow the whistle.

Those who have served, and those who still do, should be very sympathetic to Manning’s dilemma. On the one hand, standing orders and certain laws pertaining to handling classified information bound him to silence. On the other hand, yet different laws, arguably higher laws, and a sense of moral duty bound him to speak the truth. His statement before the providence inquiry suggests Manning knew he might be held accountable under those lesser laws and orders, but he rightly recognized, as his critics should recognize now, that the prohibitions against the murder of civilian journalists and firing on unarmed children trump the prohibitions against leaking classified information, and the laws forbidding our military personnel from helping a foreign government to imprison and torture its political opponents supercede laws forbidding the publication of secrets.

Uncertain though I might be of the logic by which the opponents of Manning’s selection derived their condemnation of him, I remain quite certain they are mistaken. Any who may have obscured the truth about battlefield crimes were acting treacherously, not Manning. If some in Manning’s chain of command, as evidence suggests, were misusing U.S. forces to interfere with the liberties of the very people whose democratic rights those forces were meant to secure, they were demonstrating a blatant disregard for the safety of our service members and the security of our nation, not Manning. The State Department officials who hurled insults at foreign leaders in cables they believed those leaders would never read, and who, in their embarrassment, would now hang a private, are the disgrace, not Manning. Those in the Obama administration and the military chain of command pursuing the prosecution of a man whose actions will probably save lives by rendering the Status of Forces Agreement untenable and forcing an earlier end to operations in Afghanistan make…the Armed Forces…look like a sham, not Manning. And Peters, Seefried, Sala, and all the other victims of military group-think, so insecure in the legitimacy of their own service that they must ignore the facts of Manning’s case in order to join in his pillorying, make…Gay military…and the cause of equality look like a sham, not Manning. (Sala’s use of the term “Gay military,” never mind capitalizing it, is a sham unto itself, but I digress.)

I must also quarrel with the simple sanctimony of any queer veteran or service member who would reduce their denouncement of Manning to calling him a criminal. Yes, in his testimony to the providence inquiry, Manning admitted to breaking lesser laws in the service of a higher good, but so did thousands of veterans, like myself, whose service predated Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. Our illegal but honorable service was the justification for the incremental improvement in policy represented by DADT. Likewise, once the military implemented DADT, those who did tell were also violating the law in the service of a higher good, but none who have benefited from the repeal of DADT would castigate those individuals as criminals. Instead, our communities, even many who oppose U.S. military policy, count those individuals as heroes. As a participant and organizer of many protests of the military ban, I also know that the intentional breaking of the law in acts of civil disobedience was critical to raising public awareness and shaping popular opinion so that queer service members might serve openly today. That those who enjoy the greatest advantage of such efforts would take such an uncritical view of military or civilian law truly disheartens me, and suggests a childish understanding of history.

Most troubling, though, is that queer service members and veterans would employ the Manning broke the law tactic when congress has yet failed to repeal Article 125 of the UCMJ, the article that prohibits sodomy of any stripe for all service members, queer or not, married or not. The repeal of DADT may have decriminalized calling oneself “gay,” but actually doing anything that makes one so remains a brig-time offense. While this odious law persists, Peters fights for spousal benefits, Seefried chases media attention, and Sala organizes military contingents for Pride parades. Might this be the dirty little secret compelling them all to their vehement repudiation of Manning? Is the internal recognition that their service remains a legal hoax undermining their own sense of legitimacy, like the closet case homophobe who lashes out in hatred of others because of what he despises in himself? Is their lack of courage in confronting the legal and political issue that should now most concern queer service members, the repeal of Article 125, feeding their rebuke of Manning’s moral bravery? I can’t know the answers to these questions, of course; but I would be failing my own sense of duty if I didn’t now propose them to Peters, Seefried, and Sala. Their attacks on Manning reveal a deep disrespect for the complexities of law that must always be unacceptable in individuals the state trains, equips, and licenses to kill, because such disrespect for the complexities of law among the warrior class is dangerous to all.

The second flank of my critique of Manning’s queer detractors is not concerned with the law but with the conventions of pluralism within a free civilian society, and the military’s role in protecting the freedoms that underlie those conventions. For uniformed participants in queer life to demand that civilian society conform to the rigid notions of homogeneity and the authoritarian demands of artificial hierarchies required by military life is insulting to the very idea of democratic pluralism, and casts those uniformed participants in the unflattering light of police state bullies, or, at least, children in tantrum.

I can illustrate this problem in two ways. First, consider how a secularist like me feels when pride organizations select religious leaders as grand marshals, as they reliably do in cities across the US, including San Francisco. As a class, I find the clergy altogether unfit as personal role models. I do not think religion ever serves queer freedom. To me, these individuals will never be heroes. I also sometimes disagree with the political or social views represented by such selections. But I am so grateful to live in a truly diverse community, populated by many with whom I disagree. I would never presume, as Peters, Seefried and Sala have, to suggest that pride organizations not select individuals with whom I disagree, or even those of whom I somehow disapprove. Rather, I expect that the contingent of people representing me in such roles will be diverse, and that I may sometimes even find some choices objectionable. Otherwise, I might suspect that the pride organization had failed in its responsibilities. No doubt, many queer San Franciscans are pacifists, or at least oppose militarization, but they didn’t stamp their feet and demand SF Pride rescind its selection of Dan Choi as grand marshal in 2009. Instead, they took the opportunity to discuss military politics with their queer neighbors, pulled the boas and boots from their closets, and went to the parade.

The cultural, philosophical and intellectual diversity of our queer communities enriches us all, and Manning’s critics should be eager to foster it, too. The pride organizations of large cities like San Francisco, recognizing that one person alone can’t possibly embody such diversity, typically select more than one parade marshal, and usually employ multiple means for their selection. A board of directors will likely employ different criteria in their selection than the voting public participating in a community selection process might employ. Similarly, a congress of former grand marshals will likely employ different criteria still. Finding ways to embrace the differences among us strengthens our communities in important ways, and Manning’s critics should be grateful for San Francisco’s robust efforts to do so. Indeed, one would hope that a desire to protect the freedoms that make such expressions possible serves, in some part, at least, as motivation for military service. The uniformed participants of queer life can celebrate such expressions even while disagreeing with them; to instead selfishly demand that such expressions be disallowed does not comport with the demeanor of sacrifice, and love of liberty demanded by life in uniform.

My second illustration of this problem may better appeal to the self-interest of queers-in-uniform, as it concerns their strategic position in the queer political community. For this illustration the reader must permit me a slight historical diversion. As the Navy was discharging me for homosexuality in 1987, I stood at a payphone on the quad at Naval Nuclear Power School in Orlando and called every major political organization that had ever taken any interest in queer politics or queer legal issues. I called the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund (LLDEF), the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force NGLTF), and the Human Rights Campaign Fund, (HRCF) among others. I realize now that I was naïve to think these organizations could help me in any way, but what surprised me even then was how little they seemed to know or care about the issue. On the political left where most queer alliances were forged, the plight of a Navy fag was something of a non-issue. Lambda was litigating one relevant case at the time, as I recall, and the receptionist at HRCF was sympathetic, and a volunteer at ACLU advised me to say nothing that would incriminate myself. Otherwise, they told me in no uncertain terms, I was on my own.

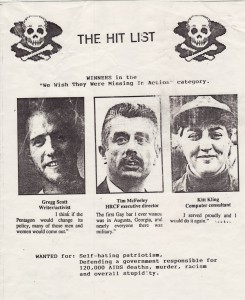

After my discharge and my return to Washington, D.C. I had the great privilege of meeting and befriending Frank Kameny. He was then the only political figure in the capital to have any sense of the gravity of the military ban on homosexuality encoded in Defense Department regulations. The queer right first seemed strangely protective of the military closet, but by the end of the decade was recognizing the need for the military to permit queers-in-uniform to serve openly, thanks in part to Congressman Gerry Studds, and HRCF Executive Director Tim McFeeley. The queer left was not only indifferent to the plight of queers-in-uniform, it was hostile to the very idea of queers-in-uniform. Several years before NGLTF inaugurated its Military Freedom Project, I sat across the desk from Jeff Levi, who would later lead that effort, and told him the story of how I was exposed as a fag and discharged from the Navy. He said not a word until I finished my story, then after a long weighted pause, he shook his head with puzzled derision, and asked,” So, explain to me again, if you’re gay, why would you want to be in the Navy?”

Over the next five years, Kitt Kling, Miriam Ben-Shalom, J.B. Collier, and I, veterans-turned–activists all, joined Kameny’s ongoing efforts to change those attitudes. By Veterans Day 1991, our efforts had united hundreds of demonstrators, representing an array of groups from the HRCF to the NGLTF marching behind a Queer Nation banner, to protest the ban on the steps of the Pentagon, but the issue remained far from a mainstream concern of what was then considered the national movement, either in D.C., or out in the states. Our communities were suffering the worst of the AIDS crisis; progressives were generally wary of US military policy in the wake of the Gulf War. In some ways, moreover, movement activists had never fully recovered from the shock of the Supreme Court’s decision in Bowers v. Hardwick, and they had every reason to be reluctant to take up the cause of lifting the ban.

After Glenn Belverio wished me dead in the queer ‘zine, Pussy Grazer, I decided to argue directly for the support of the radical queer left, of which, as a member of ACT UP and Queer Nation, I considered myself a part. I first made my case in a speech I gave during a workshop on military homophobia in Norfolk, Virginia, “Tell the Queer Who Asks Why Care,” written to address the specific objections of the queer left. I then spent the spring of 1992 repeating its key points to anyone who would listen. I argued how the military’s ban and its culture of homophobia adversely affected American civilian life, even for those antagonistic to US militarization, and how lifting the ban served the queer left’s desire for a more pluralistic civil society. I was among only a handful of activists, organizers, and elected officials making the case, but the case was strong, and eventually more and more influential voices were added to ours as the political pressure for change grew. By that fall, reporters were asking questions on the campaign trail, prompting candidate Bill Clinton to make his now-famous promise to lift the ban, in turn prompting queers from every walk of life and from across the political spectrum to vote for him that November. One year after Queer Nation had stormed the Pentagon, President-elect Clinton affirmed that he would keep that campaign promise.

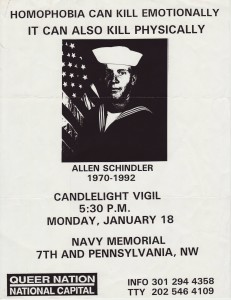

The tragic murder of Alan Schindler galvanized even pacifist and anti-military activists behind “lifting the ban.”

In those five years, from the summer of my discharge to the autumn of Clinton’s election, I had witnessed a large national movement shift from a position of indifference, even hostility, on the issue of queers-in-uniform, to a position of nearly full support for lifting the ban. Even many who identified as pacifists, and many opponents of US military policy, now agreed that the plight of queer service members was an issue our communities could no longer afford to ignore. Early in 1993, when the news of sailor Alan Schindler’s brutal murder at the hands of gay-bashing shipmates surfaced, the fatal beating seemed to tragically emblematize all the arguments of the last five years. No one who attended the March on Washington in 1993 could fail to observe the unity of the national movement on this issue. Diverse components and factions, some who were very anti-military, closed ranks in solidarity with queers-in-uniform: a pluralistic force of immeasurable political power. The rest of the story is well-told: an unfortunate compromise, seventeen years of justice delayed, an ultimate victory the full measure of which is yet unfolding; but without the alliances of diverse groups with various interests united in pluralism to lift the ban, there would be no story to tell. The right for queers-in-uniform to serve openly may not have been achieved until 2011, but the political will of the movement that achieved it was forged in 1993, and it was forged in the fires of pluralism.

I can’t imagine why those who enjoy the finest fruits of that achievement would turn their backs on the very same leftist impulses that drove queers into the streets in solidarity with them. Perhaps, they are ashamed of us, the queer comrades who fought for them and would now fight for Manning, too. Or perhaps, now that they have their full place at the military table, they fear losing it through guilt by association. I don’t demand they agree with supporters of Manning’s selection as grand marshal, although I think the facts are on his side, and speak especially clearly to those of us familiar with military law. Nor do I demand that they share my views on US military policy. I do expect them to respect the pluralist conventions of the diverse civilian society they are sworn to protect, and in which they are choosing to participate now that they are free to do so; I expect them to express their disagreement without censoring the expression of others; I expect them to recognize that, just because they are no longer bullied by the military closet, they are not now free to bully the rest of us.

Bradley Manning faced a terrible dilemma, and none should judge him lightly. Given the choice between doing the right thing at enormous personal cost, or doing the easy thing by ignoring a great wrong, Manning showed true valor. Under similar circumstances, most of us would like to think that we would choose the right over the easy, as Manning did, but, until we are somehow tested we can never be sure. So, we must imagine these aspirations for ourselves through him, holding his example close, a model for our own behavior in trials yet to come. Moved by empathy for the victims of battlefield crimes, an empathy I have speculated may have somehow emerged from his very experience of being queer, Manning bravely sacrificed self. For this, he will always be a hero to me, and for many of us, a true cause for celebrating queer pride.