I shouldn’t really be here writing these words right now, by which I don’t mean I shouldn’t be here, in my second story corner apartment in San Francisco’s Hayes Valley, typing this post, but rather, I shouldn’t be alive at all, anywhere, doing anything. I should be dead. I should be dead, incinerated to ashes and scattered to the winds, perhaps over the Seine or the Keizersgracht or the White House lawn – each had once been my wish – and long since re-integrated into the molecular and energetic fields of being that compose the universe. I shouldn’t be here writing these words right now because I should be dead.

These words, moreover, come not lightly. Neither flippant ease nor trolling provocation guide my typing fingers. Rather, I am deadly serious. I only barely survived the terminal stages of AIDS in those crucial years before lifesaving therapies became available, and, ultimately, I only survived because activists successfully compelled the makers of those new drugs to offer them, through compassionate access lotteries, to patients already too sick to participate in the trials, and I was one of those patients who won the lottery. Thus, in Aristotelian terms, one could claim the efficient cause of my survival was a combination of combinations, a cocktail of drugs combined with a mix of activist-perseverance and gambler-luck. Such is the stuff of award-winning documentaries, and I don’t deny that I owe my life, in some part, to the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), the Treatment Action Group (TAG), and randomized contingency, as much as protease inhibitors.

I am not alone, of course. Four thousand U.S. patients received the drug that saved my life in the same compassionate access lottery, and thousands of others received a different “miracle drug” through another lottery, and thousands more received the new therapies outside the U.S. Who knows how many, or how few, of us remain? Of course, I cannot speak for them, or anyone else, but my unexpected recovery propelled me on a quest to understand and give meaning to my survival. In the decades since my recovery, a more complete, and consequently more accurate explanation for my survival has emerged — a more complex narrative, and one that recognizes deeper forces operating without and within the obvious, proximate causes.

In addition to tenacity, fortuity, and the then-new drugs themselves, any complete enumeration of the efficient causes of my survival must include my privileged access to healthcare, generally, and the abilities of my determined physician and friend, Dr. Douglas Ward of Washington, DC, specifically. Without such care I never would have survived those years before hope, or those months before the selection of my lottery number. I was also willing to break the law, and use marijuana to help combat severe wasting. Without Cannabis, I would surely be dead.

Add to this list all the other prophylaxes used to fend off deadly opportunistic infections, the researchers who developed those drugs, the non-human animals they tortured and killed in the process, the companies that manufactured those drugs, the employees of those companies, the distribution systems that delivered the drugs to my local pharmacy, the pharmacists who dispensed them, the educational systems that prepared all those individuals to perform their assigned roles, the governmental agencies that assured I could afford them, and the taxpayers who subsidized their cost – and, still, the enumeration remains incomplete. Truthfully, to account comprehensively for the means of my survival requires that I extend recognition to the entire industrial economy, to the climate-changing carbon it spews, to the reef-smothering agricultural poisons it dumps, to all the species threatened by and lost to our runaway civilization, to the denigrated ecosystems that once supported those species, to the dying planet itself.

I am responsible for that. I must answer for it. To be a long-time AIDS survivor is to be a planet-killer. My handful of pills reminds me twice a day. These are not the products of a sustainable human society. Although medicating death away at any cost may seem to somehow ennoble our earth-hating civilization (Homo sapiens at our best, right?) I suspect the polar bears, expected to largely disappear in the next fifteen years, will take no consolation in the fact that some of the greenhouse gases that destroyed their world were emitted to save an old AIDS-ridden fag like me. No, whether the Arctic thaws because of industrial medicine or industrial war will matter not at all to the polar bears. Moreover, the seemingly ennobling endeavor of industrial medicine illustrates the profound tragedy of our deluded civilization as industrial war cannot, for to wage war means to waste and destroy. War makes little pretense to disguise itself. It no longer even pretends, as it sometimes did in the last century, to seek some enduring peace, some permanent end to war. Now, wasteful, destructive war is forever, and we don’t even bother to pretend otherwise. But industrial medicine calls itself health care, pretending it has something to do with wholeness, pretending it’s not just as ecologically violent as industrial war, pretending its own war, its supposedly merciful war on death, continues to make sense on our perilously overpopulated planet.

Years ago, after discovering the deep ecological philosophy of Norwegian mountaineer Arne Naess, but before discovering the devastatingly honest books of Derrick Jensen, I wrote of this quandary more delicately:

I awake each morning with a paradox, and with it I retire every night. A peril to my life has revealed to me the immanence of earthly nature, but the same peril can only be eluded through the gravest offence to that very immanence. I am bound in a Faustian bargain with an unsustainable fossil fuel economy, and twice a day, swallowing a handful of pills aggregately known as Highly Aggressive Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART,) I must also stomach the hard truths of my entitlement.

I have AIDS, and so I have for fifteen years. I am very lucky. I was infected long ago, and in the clock’s last ticks of my eleventh hour, effective therapies availed themselves to me. With other fortunate comrades of those embattled years, I rose up Lazarus-like from my death-bed, not winged by some messianic miracle but rather snatched from the bier by the perfectly-machined pincers of oil-energy technology – a petrochemical rescue – a medical redemption that finally saves no one, promising only overpopulation, a mean living, and a miserable prolonged death.

Make no mistake. I am ever so grateful for this life, this time, and especially this rare view through the veils of the sacred cycles of time and place that define our earthliness. But I also understand that if human beings are to survive, we must live in different ways, more sustainable ways, more earthly ways – and those ways probably don’t include HAART.

The “hard truths of my entitlement” have weighed heavily on me of late. While I welcomed the recent news that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have begun releasing their research chimps to a retirement sanctuary in Louisiana, I remained disappointed that the last congress failed to pass the Great Ape Protection Act. While I welcomed the president’s State-of-the-Union threat to direct the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to use its current authorities to regulate greenhouse gas emissions if congress fails to act, I’m discouraged that the Department of State, in a Supplementary Environmental Impact Study since revealed to have been written by oil industry contractors, failed to use its authority to halt the construction of the Keystone XL Pipeline. While I welcomed the video of tens of thousands of protesters marching on the White House to demand serious action on climate change, especially a halt to the construction of the Keystone XL Pipeline, I was saddened to see so many protesters whose signs and props suggested they still mistakenly believe wind farms and solar panels will save us.

Such global concerns in the news have muffled my crowing over small queer victories of recent weeks. The inclusion of queer and indigenous people in the Violence Against Women Act, the amicus curiae briefs supporting repeal of DOMA and California’s Prop 8 filed with the Supreme Court by the White House: such is the expected fodder for these pages. But these victories, though real and meaningful, will be rendered merely pyrrhic should humans fail to recognize the planetary emergency we now face.

To be clear, I believe these things are all connected in ways queerkind has largely failed to realize. While intuitively, even academically, we acknowledge how the power dynamics of “othering” queer men is somehow an iteration of the “othering” of women which, in turn, is somehow an iteration of the “othering” of wild nature, including indigenous people, we have not successfully organized our politics, ethics, or culture around this knowledge. “Othering” is a requisite enabling mechanism in the ongoing destruction of this earth, wild people, non-human animals, and our natural selves – and queerness is perhaps the only antidote.

For me, identity politics remain relevant on a dying planet not because of the short-term legalistic gains made for small groups of slightly-less-privileged people in rich western nation-states, but because how we identify, how we imagine our most expansive selves and what we include in that extension of our identity define our priorities. While Naess hints at the hopeful prospect of humans developing a sense of ecological self, expanding our identities to encompass the land base, watersheds, and food sources that sustain us, Jensen’s words on the topic of identity are unflinchingly dark:

If you perceive yourself as a consumer, consume you will. If you perceive yourself as a “new and thoroughly superior predator,” you will act like one. If you perceive yourself as a member of a species that can act no other way than to destroy your landbase, that is what you will do. If you perceive yourself as the “apex” of evolution, you will try to climb to the top of something that has no top, and you will crush those you perceive as being beneath you. If you believe you are separate from your landbase, you may believe you can destroy your landbase and survive, and you may very well destroy it. If you perceive yourself as entitled to exploit those around you, you will do so.

One of the stated premises of Jensen’s two-volume Endgame, the source of the preceding quote, is that our culture’s sense of self is no more sustainable than our current use of energy and technology. What about queer subculture’s sense of self? Is it sustainable? Do we identify with the Wapishana, Yuqui, Fleicheros, Guaja or dozens of other yet-wild peoples subsisting in ever-shrinking refuges as civilization encroaches all around? Or do we identify with the celebrities who dominate our commercial culture? Do we identify with the non-human animals struggling to survive in the ecosystems our civilization continues to denigrate? Or do we identify with the superficiality of fashion, the excesses of materialism, and gratuitous technology?

Jensen has gotten under my skin, and having trod so near to death, only to return, I can’t help but identify with the shining polar bears, and the living soil, and the wondrous coral reef. I can’t help but identify with Jerom, a chimpanzee who was taken from his mother as an infant and confined to the Yerkes National Primate Center in Atlanta. There, researchers repeatedly and pointlessly infected Jerom with HIV, and there, in 1996, just as I was discovering a second life, Jerom died at the young age of fourteen, having suffered miserably for years. Researchers learned nothing from these experiments except that chimps were generally not useful to AIDS research; HIV infection did not progress to AIDS in chimpanzees as it did in humans. Jerom was an exception, and though researchers failed to find in him their holy grail, that is, an identifiable opportunistic infection, Jerom grew very ill indeed, suffering chronic diarrhea and severe wasting like everybody I else I knew who ever died of AIDS.

As one who has held a dying friend in my arms, I must also identify with Jerom’s caregiver and friend, Rachel Weiss, who quit her job after Jerom’s death and, so, was free to tell his story. The compassion she brought to Jerom’s care provided rare reprieve to his tortured existence. However many times I read her moving account, it yet brings tears. To such cruel wrongs as these may I never be inured.

In the years since my recovery, I can trace my path through a process of recognizing the reasons for my survival through distinct periods of recovery, one evolving into the next, in a phased homage, an obeisance to the first and second causes. Without failing to acknowledge the efficient causes of my survival as I already outlined, I assumed my attitude of homage to explore the material and formal causes of my survival. This attitude accorded to the rubrics of gratitude, accountability, and generosity, meaning each phase of the obeisance represented an intentional practice of identifying and recognizing a reason, or cause of my survival as the object of my gratitude, then defining my accountability to the object of my gratitude in terms of my specific future responsibilities to the object of my gratitude, and finally, attempting to fulfill those specific responsibilities with generosity.

Remember, upon discovering I would live after believing I would die, I had no plan. My bucket list had been enumerated, edited for time, adjusted for loss of capacity, edited again for time, and so on, until nothing remained. I don’t remember anyone having a plan. “Hey, PWA. You just cheated death. What are you going to do next?” Going to a theme park hardly rises to the occasion. Since no one knew how long those protease-inhibitor-driven recoveries would last for the once-near-dead like me, long-term planning seemed like an inappropriate paradigm, anyway. So, lacking a plan, I deliberately applied a practice. (I have not overlooked that the acronym for the rubrics of gratitude, accountability, and generosity would be G.A.G., and I fully recognize the gag-inducing potential of anything smacking of self-improvement cliché, but I welcome any ridicule it invites as the price of my authenticity and as harbinger against my own sanctimony.)

I wish I could say I was so successful in my practice that anything I’ve ever done has been adequate to express even a fraction of the gratitude I feel, or return even a fraction of the generosity I enjoy at the hands of brother, friend and stranger alike. I can never make a full accounting for my undeserved turn of fate. The homage to the causes is but my stumbling, leaning, and lurching efforts towards some adequate expression.

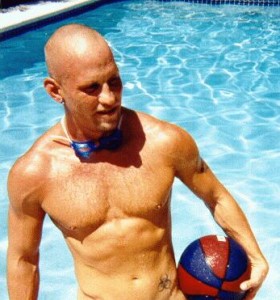

The first period of homage celebrated my resurrected body. After only a few months taking protease inhibitors and upon the return of my vigor, I began exercising, eating healthier foods and enjoying them more than ever before, and sleeping until I awoke without an alarm to be always perfectly rested. I left Washington, D.C.’s swamp-winters and blazing summers for sub-tropical South Florida where I spent more than a year without any worry in the world other than the optimization of my own health, thanks to my generous friend Chris, who let me live in his comfortable home as an honored guest. Like a spa-resident’s, my days began with long bike rides, possibly to one of the beaches, or to Fort Lauderdale’s extravagant public swimming pools, or to the gym. Relaxed afternoons faded into warm nights spent sharing healthy salad-centered meals, then to be followed by long sleep-filled nights. I had never felt or looked better; in Florida, I even quit smoking tobacco. In homage, I had renewed my relationship with the substance and shape that are my body; I made and kept commitments to myself about my personal habits, and became accountable to my constitution, whatever genetic or developed physical advantages had made my survival possible. Without this body, I would be dead. I am accountable to this body.

I could not forget how my near-death experience had opened my mind to the interconnectedness of the seemingly disparate, and the permeability of apparent boundaries. As if in fulfillment of the promise of that insight, I now discovered that the more gratitude I showered on my physical self, the more expanded grew my sense of self and the scope of the gratitude I felt; having depended so heavily on friends and family and community during my illness, I could no longer perceive myself as a wholly autonomous organism in the way I might once have. I now understood viscerally the meaning of being a social organism, existentially interdependent with others, whom, as parts of one’s expanded self, could no longer be “othered.” The perception shifted most easily among biological relations, whom, by virtue of shared genetic and cultural birthrights, society permits us to consider extensions of ourselves. Among friends, the shift in perception was more unexpected, and for its greater unlikelihood, perhaps all the more revelatory.

The progression, from perceiving friends – like dear J.B., and openhearted Chris, and brilliant Dr. Doug – as existentially interdependent to perceiving my larger community as existentially interdependent, required only a subtle shift further in my perception of my self as a socially interdependent creature. My conscious awareness of this shift marked the transition from the first period of my recovery to the second, and my homage to the first and second causes, understood as my own physical being and predictably manifest in glowing physical vitality, yielded to my homage to the first and second causes as revealed by my shifted perception: the material revealed as energetic and shared, no longer contained by my mortal individuality, and the form revealed as social and connected, no longer bounded by genetics or personal loyalties. Again, following the rubrics of gratitude, accountability, and generosity rather than any plan, my second homage realized itself in several years of volunteerism, activism and community organizing in South Florida. I knew no other way to say thank you to my family, friends, and community, but to give my time and my modest abilities back to communities of people like those who had sustained me, and in advancement of the ideas those communities valued.

Unrecognizable in some ways from the activism I had practiced in Washington. D.C as I had grown ill, my community endeavors in South Florida were more measured, thoughtful, consistent and mature than my earlier engagements with politics, even if they were sometimes manifest in outrage as well as service; my shortcomings notwithstanding, there I became the best community member, the best social and political self, I had ever been. Without community, I would be dead. I am accountable to community.

In 2003, I left South Florida for California, where I enjoyed the open-handed hospitality of another generous friend, Dennis. The reasons for the move were many, and some were more complicated than others; in one sense, I was following my gratitude towards an expanding sense of community, one that now entailed entire ecological systems, food sources, watersheds, and wild places. I vaguely hoped I might live in closer connection to my own food. But just as my practice during the homage of the first period of my recovery led to insights that transformed my understanding of my own substance and shape, thus yielding to the second period of my recovery, so the rubrics of gratitude, accountability, and generosity as practiced during the second period of my recovery transformed my understanding of community, expanding it to encompass the ideas that bind communities together, the shared cultures of places, beliefs, and values that shape communities, and the collective wisdom embodied by those communities. This insight turned me again towards self, but now to attend my emotional, intellectual and intuitive self. Here in California, I have spent years improving my mental health, resuming my education, and exploring my spirituality, pursuing all according to my own individuated and heterodox curricula. Though the rubrics remain unchanged, this homage manifests as reading, listening, studying, learning, and meditating. Just as I achieved my finest physical self, or being-self, by practice of the rubrics during the first period of my recovery, and my finest social self, or communing-self by practice of the rubrics during the second period of my recovery, so I sense I am now shyly approaching my most knowing-self. Without this mind, I would be dead. I am accountable to my mind

With the rubrics propelling me towards new insights still, I feel myself already in the flush of transition yet again. Perhaps this blog is among its outward signs. My homage continues, now turning imperceptibly towards collective consciousness, yet another surprising expansion of my sense of self, and one that obligates me even further to Jerom and the other chimps like him, and the rhesus monkeys who have replaced the chimps as HIV research subjects of choice. At its core, the homage to the first and second causes remains homage to an expanding sense of self, a recognition and reverence of multidimensional identity, a queering, or un-othering of everything.

Without the shining polar bears I would be dead. I am accountable to the shining polar bears.

Without the living soil, I would be dead. I am accountable to the living soil.

Without the wondrous coral reef, I would be dead. I am accountable to the wondrous coral reef.

I can’t be sure where the rubrics will lead me, but I imagine some day, through my interior journey as charted by my evolving homage to the material and formal causes of my survival – my expanding sense of self – or the outward journey as charted by the obvious, efficient causes with which this post began – tenacity, fortuity, and miracle drugs – I may yet discover the fourth and final cause, a purpose to my survival, my reason for being. Until it reveals itself to me, I can only strive for gratitude, accountability, and generosity. I owe it to my expanded sense of self. I owe it to my family, and friends, and community. I owe it to my landbase, and watersheds, and food sources.

And I owe it to Jerom, because, without Jerom, I would be dead. I am accountable to Jerom.