In the rituals of human courtship and mating, questions of intention appear to have always mattered, and the recent and ongoing debates about marriage equality demonstrate they matter still. I use the word intention, here, as it is commonly understood, to mean purpose or aim, but its more esoteric meanings from medicine, neurobiology, theory of mind research, religion, and spirituality, may also relate, revealing as they do how completely the notion of intention is enmeshed in earthly nature. Many avian and mammalian species require elaborate demonstrations by prospective partners before assenting to mate, and what biologists call animal intentionality emerges in the evolutionary record long before any shotgun-toting patriarch asked of his daughter’s suitor, “Exactly what are your intentions, son?”

In late March, as the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) prepared to hear three days of argument in the two cases considered potentially determinative of future marriage rights in the U.S., Salon columnist Sally Kohn ignited a debate with conservative MSNBC commentator S.E. Cupp when she expressed misgivings about the reasons some conservatives were citing for their support of marriage equality. Although Kohn never used the word, she was talking about intentions.

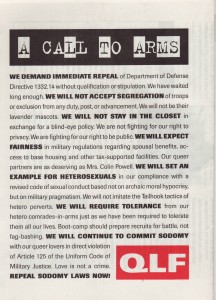

Kohn argued that queerkind should be wary of conservative support rationalized by moral claims about the institution, itself, rather than moral claims about equality, inclusion, or freedom of choice. She wrote, “To the extent Republican support for gay marriage is based on imposing restrictive and regressive conservative social norms, it ultimately hurts gays — and all of us — more than it helps.” Kohn reminded readers that a diverse coalition of activists expressed concern about this very danger in the 2006 statement, Beyond Marriage, and she quoted one of its seminal claims: “Marriage is not the only worthy form of family or relationship, and it should not be legally and economically privileged above all others.” Cupp, describing in her response the “overtly conservative belief” she said Kohn was rejecting, entailed as succinct a conservative case for marriage equality ever there was: “…that marriage is a stabilizing social construct that should be encouraged…”

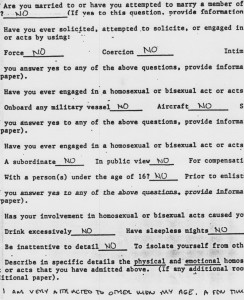

That lawmakers might intend to use marriage law to impose social or moral norms, as the Beyond Marriage signers feared, is hardly academic, as Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg highlighted from the bench, on the first day of arguments in U.S. v. Windsor, the case that challenged the constitutionality of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), when she read from the House of Representatives’ 1996 Report on the passage of that law:

Civil laws that allow only heterosexual marriage reflect and honor a collective moral judgment about human sexuality. This judgment entails both a moral disapproval of homosexuality and a moral conviction that heterosexuality better comports with traditional (especially Judeo-Christian) morality.

Those words elicited audible gasps from court spectators, although congress’ morality-shaping intentions should surprise no one who remembers the 1996 debate, and also bolstered the opinion of the court that Section 3 of DOMA, which narrowed the definition of “marriage” in the United States Code to mean only a union between a man and a woman, violated the Fifth Amendment (an opinion propitiously released on the tenth anniversary of Texas v. Lawrence, Justice Scalia’s dissent to which famously foreshadowed such an outcome.) Writing for the majority in U.S. v. Windsor, Kennedy cites the congressional gasp-worthiness:

The history of DOMA’s enactment and its own text demonstrate that interference with the equal dignity of same-sex marriages, a dignity conferred by the States in the exercise of their sovereign power, was more than an incidental effect of the federal statute. It was its essence.

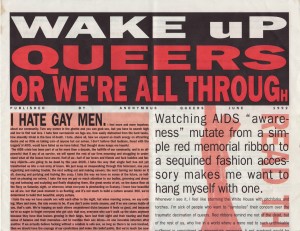

Indeed, much of the social agenda of the conservative movement is precisely so intended, and observers can’t help but recognize the connection between conservative disapproval of sodomy and conservative disapproval of abortion, both finally a disapproval of all non-procreative sexual pleasure. Columnist Dan Savage recognized this usually unstated but somehow obvious connection on Up with Chris Hayes at the end of March, when he said, “Gay is the new abortion.” Savage made the point that marriage equality advocates will have to defend every advance just as women must continue to defend their reproductive freedom long after Roe v. Wade; mere court rulings will not dissuade social conservatives from their struggle against what they consider sexual perfidy:

Abortion, access to birth control, women’s freedom, women’s rights, gay rights, it is all about sexual control. And it is all — the thing that links them all is kind of this anger about sexual — recreational sex. You are having abortions because you had sex for fun; you didn’t want to have babies. You’re using birth control, which Rick Santorum has a problem with, because you’re having sex for the wrong reasons, which is 99.99 percent of the sex that human beings have, which is for fun and intimacy and connection and release. And that links gay sex, too. That’s why they’re against all — abortion, birth control, gay people, gay sex, gay marriage all linked by this religiously inspired anger at people who are having sex for fun, not for God.

Significantly, not all Republicans now supporting marriage equality base their support on the conservative nature of the institution, as Rob Portman did. Some, like Jon Huntsman, do frame their support, however belated, in terms of individual liberty, and equality under the law. Similarly, not all Republicans who have not expressed support actively oppose marriage equality. Many, like Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker, retreated early to the refuge of a states’ rights argument, thus evading the real debate. Nonetheless, with so many Republicans hinging their opposition to marriage equality on the moral disapprobation of “sex for fun, not for God,” and the ones experiencing changes of heart arguing the conservative case for marriage equality – “…that marriage is a stabilizing social construct that should be encouraged…” – circumstances do seem to conspire towards the difficulties Kohn outlined: a paradigm of beliefs and attitudes that together create a subtle coercion to marry, possibly for reasons that hue not to the authentic selves of the participants. Intentions, anyone?

Subtle coercion seemed to worry activist Scot Nakagawa, also, in the widely read essay he posted the same week. Nakagawa addressed concerns very similar to Kohn’s, but did so with an eye on the intentions of movement activists as well as newly-supportive conservatives. Nakagawa argued for supporting same-sex marriage as a civil right but not as a strategy to achieve structural change, his titular premise, and cited the potential pitfalls of the “model minority” strategy the “mainstream LGB movement” is pursuing with success, including the danger of exploiting the same us versus them dynamic that operates to oppress across all the usual axes, and will undoubtedly persist in so doing, long after full marriage equality throughout the states is won. But Nakagawa was especially persuasive when he addressed one of my own personal fears, one I have failed to articulate as well as he. Nakagawa wrote:

Also troubling is my sense that the current strategies ignore something about marriage rights that ought to be obvious to anyone excluded from them, especially when that group is arguing that being excluded has real, material consequences. That is, that we are arguing to be able to use marriage as a shield against wrongs that no one, regardless of sexual orientation or marital status, should suffer. No loved one should be excluded from survivors (sic) benefits and pensions, end of life decision-making, hospital visitation, and the many other family rights reserved for married couples. And when we argue that being able to wield this shield is a right we deserve because we conform with the values of good people, that shield can become a weapon against those who are still excluded.

Thus, to seek marriage equality for the wrong reasons is not only to divert queer energies and resources away from the ongoing endeavor of transforming the culture, but also to invest those energies and resources in the reinforcement of the same heteronormative culture queer activists seek to transform. Here, marriage equality advocates risk the emergence of a corollary to heteronormativity that one might well call homonormativity. Enter a world where families, friends, coworkers and neighbors expect certain queerkind of certain backgrounds to pair-bond and marry, a world of “good gays” and “bad gays,” a world where the hegemony of heteronormativity remains unchallenged, even in its homonormative variation, a world that changes queerkind, rather than a world changed by queerkind.

I agree fundamentally with Kohn, reluctantly with Savage, and readily with Nakagawa. Kohn is right to be wary of the intentions of newly-supportive conservatives. Savage is correct in his estimation of the intentions of most socially conservative politicians and activists. Nakagawa is eloquent on the moral dangers of assimilation. Yes, intentions matter. They matter because they describe expectations. They matter because they express identity. They matter because they shape outcomes. So, leaving aside the intentions of marriage equality advocates, their socially conservative opponents, and their newly supportive conservative allies, what of the intentions that will ultimately matter most? What of the intentions of those who would marry?

With the demise of the central provision of DOMA, and the resumption of legal same-sex marriage here in California, the question has become all too personal for me, while remaining somehow predictive of the trajectory of our shared queer future. So, before I wed my own special friend of the last ten years, I must ask myself: exactly what are my intentions?

Historically, people have wed for many purposes, and what were once the most compelling reasons seem at once meaningless to our modern queer lives. Marriage as means of political alliance, marriage as guarantor of paternity, marriage as means to exchange daughters as property, and marriage to secure religious approval for sexual relations will seem to most queers as archaic, indeed. Yet, these intentions continue to shadow contemporary reasons to wed, and for some will always taint the institution as inherently patriarchic, materialist, sexist, and religious. If marriage’s new adherents sincerely mean to liberalize the institution by their participation, as I’ve heard many queer proponents for marriage equality claim, then they must strive to cleanse the institution of these taints by every reasonable means. That project –to modernize marriage for everyone – possibly requires the would-be-wed to undertake an unflinching examination of their own motives. Minimally, such self-examination might lead to more honest and satisfying matches, and could strengthen meaningful political efforts to expand and defend marriage rights. Optimally, it might help nudge the movement away from the white, middle class pitfalls Nakagawa cited, perhaps even helping to re-contextualize the movement within a larger framework of social, economic, and environmental justice for all.

Naturally, people do most things they do for more than one reason. Multiplicity of pathways and redundancy of means are patterns no less enmeshed in our biology than intentionality. One of the greatest challenges of mindfulness is to recognize all those reasons rather than only the comfortable ones. Human survival mechanisms may permit a suppression of our less-than-noble intentions, but the psychic costs can be dear, and cavalier suppression of the inconvenient may lead to some very unreliable thinking.

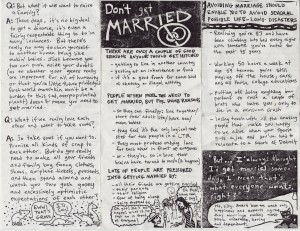

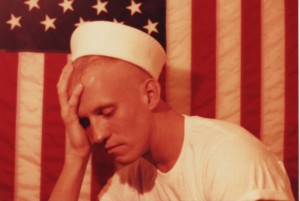

- Artist Sy Wagon offers good advice: “Don’t get married.”

In the late 1990’s, amidst the gay backlash to DOMA, San Francisco Bay Area artist and Baitline publisher Sy Wagon, then residing in Boston, produced a comically blunt pamphlet aimed at just such unreliable thinking on the topic of marriage. The banner heading the front center panel advises simply, “Don’t Get Married,” then lists the few “good reasons anyone should get hitched,” before listing the “dumb reasons” for which people often do; another panel describes the “life-long disasters” that can be avoided by avoiding marriage. But one finds the best bits of the pamphlet in the five remaining panels of Q&A, including unpretentious advice about not depending entirely on one person for all one’s needs, the unlikelihood of fateful pairings, and why lovers should simply enjoy it while it lasts rather than scheming for permanence. More than a decade later, this all remains good advice for anyone, regardless of the sex-genders involved in their relationships, but I suspect it is also advice that was either never considered or altogether dismissed by the yet uncounted same-sex-gender couples who rushed to California altars and arbors for late summer weddings in this watershed summer of weddings.

Why did they do it? What were the intentions, for example, of the couples lined up at San Francisco Civic Center throughout the Pride celebration, and for weeks thereafter, to become legal spouses? Plainly, the question answers itself in at least one part, but legality is only one of a handful of reasons most people cite directly or indirectly when speaking to newspaper and television reporters about why they want the right to marry. Equally important seem to be the social legitimatization and approval that proceeds from that legality; is not social affirmation precisely what Edie Windsor meant when she talked about the “magic” of marriage from the steps of the Supreme Court? Her extemporaneous yet instantly iconic remarks seem to me to be describing the power of social affirmation:

I wanted to tell you what marriage meant to me. It’s kinda crazy. We lived together for forty years. We were engaged with a circle diamond pin because I wouldn’t wear a ring because I was still in the closet… I am today an out lesbian… who just sued the United States of America, which is kinda overwhelming for me. When my beautiful sparkling Fia died, four years ago, I was overcome with grief. Within a month, I was hospitalized with a heart attack, and that’s kinda common; it’s usually looked at as “broken heart syndrome.” In the midst of my grief, I realized that the federal government was treating us as strangers and I paid a humongous estate tax, and it meant selling a lot of stuff to do it, and it wasn’t easy. I live on a fixed income, and it wasn’t easy. Many people asked me, “Why get married?” I was seventy-seven, Fia was seventy-five… and maybe we were older than that at that point, but the fact is that everybody treated it as different; turns out marriage is different. And I’ve asked a number of long-range couples, gay couples, who…got married, and I’ve asked them, “Was it different the next morning?” and the answer is always, “Yes, it’s a huge difference.” When our marriage appeared in the New York Times, we heard from literally hundreds of people, I mean, little playmates, and schoolmates, and colleagues and friends and relatives, all congratulating us and sending love because we were married. So it’s a magic word. For anybody who doesn’t understand why we want it and why we need it… it is magic.

So the legality seems to bestow permission for people to express their social approval: magic.

Similarly, from the legality, especially, and from the social legitimization, at least indirectly, a potential for greater economic parity proceeds. This motive to marry is a powerful one for many; it was for economic parity under the United States tax codes that Edie Windsor first sued. (Even Don’t Get Married agrees that money is one of the few “good reasons anyone should get hitched.”) These three categories of motives to marry – legality, social affirmation, and economic parity – together comprise a complex of what we might call public intentions, a complex that recognizes marriage as a change of public status for the purpose of legal, social, and economic relations.

More private reasons also prevail. Though less openly discussed, sometimes evident only in subtext, these categories of reason seem to bifurcate between those of individual constraint and those of personal commitment, those addressing our need to enforce exclusivity, in other words, and those addressing our need to enforce permanence. This complex of private intentions recognizes marriage as a change in private status for the purpose of domestic, emotional, and sexual relations

The pitfalls that might stymie any of these good intentions, public or private, are more obvious in some cases than others, but the would-be-wed would be wise to beware. Certainly, departures from private intentions seem to cause the most heartache, but these, at least, queerkind can negotiate for themselves. Promises of exclusivity and permanence need not be requirements to marry, and one suspects, based on the attitudes of the young, they will ever be considered less so. Provided all parties are clear on both expectations of personal constraint and extent of personal commitment, why should a marriage require exclusivity and permanence? Undoubtedly, some men may desire exclusivity as protection against sexually transmitted infections like HIV, and for them a traditionally exclusive marriage might be reassuring. Also, I have heard female couples parenting children together express an understanding of marriage as a promise for at least semi-permanence, adequate to see children grown. But these needs do not apply to all the would-be-wed.

Pitfalls to the successful realization of public intentions may be a less obvious cause of personal pain, but these traps, in their own way, may be the more insidious. Marrying for social approval, for example, can prove problematic for anyone whose private intentions are untraditional. I know of at least one instance in which a man was unable to disclose his recent HIV diagnosis to his mother, formerly confidante in all things, because it would reveal the non-exclusive reality of his marriage, a marriage that had marked a turning point in his parents’ acceptance of his partner of many years. “That approval just meant so much to me,” he told me one day in Dolores Park. “How can I throw that away?” Moreover, and perhaps counterintuitively, the collective effect of queer multitudes marrying largely for social approval will likely serve to reenforce the same prejudicial socio-cultural dynamic that for so long heaped disapproval on those same multitudes, and disqualified same-sex-gender couples from the office of civil marriage.

Queerkind may someday find certain aspects of legality bittersweet, too. Should conservative states like Mississippi, where I grew up, be finally budged into the twenty-first century, one can easily imagine its other conservative marriage laws prohibiting adultery, fornication, and cohabitation being enforced against same-sex-gender couples in unfair ways, just as so many southern states simply applied a double standard in the application of the criminal code once deprived of Jim Crow by the federal courts. One can likewise imagine conservative states taking a page from the anti-abortion playbook, writing new laws intended to raise the threshold to marry for same-sex-gender couples, or trap laws that make it effectively impossible for same-sex-gender couples to marry in those states.

No doubt Kristen Welch and Jenna Lockwood of Picayune, Mississippi were listening when Edie Windsor described marriage as magic from the steps of the Supreme Court, but they were conjuring magic of the political kind in mid-July when they walked into the Pearl River County Courthouse with eleven other same-sex-gender couples, and applied for a marriage license they knew would be denied. According to the Boston Globe, legal concerns like recognition by the Air Force for the purpose of spousal benefits, and the resulting economic advantages, were most important to the pair, but the magic of social approval figured, too, at least emotionally. Of Welch, the Globe wrote:

One set of grandparents has quit speaking to her. In advance of her 10-year high school reunion, some former classmates, after learning she was in a relationship with a woman, have posted Bible verses on her Facebook page. “We haven’t been openly harassed as a couple but if looks could kill, we’d be dead,” Welch said about holding hands with Lockwood in public, which they’re mindful not to do too much.

However wary of marrying for social approval I may be, I do recognize the magical power of marrying, in the sense that a wedding or hand-fasting is certainly a magical process. To gather a group of people together, say prescribed words about collective intentions, participate in symbolic rituals, share meaningful music, and feast in celebration is to follow an ancient rubric of magical transformation, often entailing both outward and inward manifestations. Such processes depend mightily on intentions, said by some who study magical craft to be the basis of all magic, or at least a singular thread common to its practice in all its diverse expressions. For the magic to work, one must vet ones intentions thoroughly, and articulate them plainly. Knowing ones true intentions is the first step in any spell.

Likewise in the ongoing socio-cultural project of the queering of marriage: to question oneself about one’s own intentions, to disclose them fully to one’s prospective spouse, and to expect one’s prospective spouse to undertake a similar self-scrutiny seem to me necessary first steps, and processes critical to any hopes that queer socio-cultural values would transform the institution of civil marriage, rather than the institution of civil marriage transforming queer socio-cultural values.

Such were the thoughts of marital intention crowding my head in early spring when my younger brother, Gordon, and his partner of the past three years, Elizabeth, phoned me to ask if I would officiate at their down-home, do-it-yourself wedding, taking place later today. Their request reminded me that this need for the would-be-wed to scour their souls of hidden or false intentions is not unique to queerkind; because heterosexism is as much about the “sexism” as the “hetero,” such a self-assessment well serves anyone who would enjoy some of the benefits of legal marriage while avoiding the sex-gender-based assumptions that historically underlie it. Strong independent women like Elizabeth have no business hiding behind a veil to be “given away” by their fathers, either ceremonially, metaphorically, or in fact. The reminder also served notice: the project one might call the queering of the world promises a healthier, liberated sexuality for everyone, not just those whose sexual desires and sex-gender identities do not conform to heterosexist expectations.

Since the repeal of Section 3 of DOMA, three more states have agreed to recognize same-sex-gender relationships under their marriage laws; a total of fourteen states now permit same-sex-gender couples to marry. Some observers believe that achieving full marriage equality throughout the states is only a matter of persistence and time. Inevitable though such equality may be, we need not accept as inevitable a new paradigm of normalcy that continues to ignore the intersection of sex-gender, race, class, and abilities with the experience of queer oppression and continues to exclude, disadvantage, or discount unwed families. In essays posted since the DOMA ruling, Nakagawa, for one, has not relented in making these points. On the day of the decision, he reminded his readers that in the very same week of the DOMA ruling, the court had “effectively neutered the Voting Rights Act,” and undermined affirmative action in a ruling involving admissions to the University of Texas. Of these rights — voting, having access to education, and marrying — Nakagawa rightly asks, “which are more fundamental to a functioning democracy?” On the day following the decision, he wrote:

While most of LGBT America celebrates the legal defeat of the Defense of Marriage Act, some of us are finding this moment bittersweet. We recognize the decision is a real and meaningful victory, but we’re worried about what this victory means for those of us who wish to exercise the right not to marry, and about whether winning this right will diminish the transformational potential of the LGBT movement.

When I read those words, I felt as though Nakagawa was speaking for me, and many people I know. Marriage equality activists and organizers must be candidly reminded of these concerns as they forge ahead, state by state, or, in states like New Mexico, county by county. Yet, perhaps the greatest challenge falls to those who would themselves be married: to undertake a careful examination of their own intentions, the intentions that describe their expectations, define their identities, and will shape their outcomes. Perhaps the queerest among them will even recognize that transforming the institution of marriage itself may be the most honorable intention of all.