Last month, when I cheered the decision by US Marine Corps’ lawyers to assert the rights of marines’ same-sex-gender spouses to participate in military spouses clubs, I never expected Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta to follow the marines onto the beachhead so expeditiously – as he did today with his announcement that the Department of Defense (DoD) will significantly expand benefits for the domestic partners and spouses of queer service members. Although the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) prohibits the DoD from expanding health care, housing and survivor benefits to queer spouses, the executive director of OutServe-Servicemembers’ Legal Defense Network (SLDN), Allyson Robinson, calls the expansion “substantive,” praising Panetta for doing nearly all he could while DOMA remains in effect. Fully implementing the changes may require as long as eight months, according to the DoD, hardly soon enough for the family of U.S. Army Chief Warrant Officer Charlie Morgan, whose opposition to DOMA and advocacy for queer spousal benefits elevated her to national prominence before she succumbed to breast cancer. Morgan died yesterday.

Central to today’s announcement is the plan to issue military identification cards to same-sex-gender spouses and partners. The military identification card is integral to life in the service; without it, one can’t freely come and go from a spouse’s workplace, use recreational facilities like gyms, swimming pools and tennis courts shared by all other military spouses, attend work-related social functions at mess facilities, or participate in spouses clubs. The officers’ spouses club at Fort Bragg justified its exclusion of Ashley Broadway on precisely this: Broadway didn’t carry a military ID.

Panetta’s announcement struck me as especially auspicious today because of a personal anniversary. Twenty-six years ago, on 11 February 1987, after almost two years of training and only weeks before I was scheduled to graduate from the Naval Nuclear Power School (NNPS) in Orlando, Florida, the Naval Investigative Service (NIS) summoned me to its offices where agents informed me they were investigating me for sodomy. Military legal procedures did not require the agents provide me any other information, and I refused to say anything until I’d spoken with a lawyer. I walked out of the NIS office with pounding heart, racing mind and the creeping recognition that my navy life was about to end. Standing at one of the open-air public telephones lacing the NNPS quadrangle, I dialed long distance information and obtained the phone numbers for Lambda Legal Defense Fund in New York City and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force in Washington. I knew I wasn’t the first fag to be drummed out of the military, so I thought someone must know what I should do.

My situation wasn’t nearly so grave as it might have been only a decade before. Upon assuming the presidency, Ronald Reagan had implemented a revised policy concerning homosexuality, a revision originally drafted by the DoD under Jimmy Carter. The Carter administration had been looking for ways to save money. The previous, harsher policy always denied honorable discharges to members separated for homosexuality, thus limiting the veteran’s benefits they could claim; many sued to upgrade the characterizations of their discharges, and often won, all at considerable taxpayer expense. As attitudes towards homosexuality shifted in the late 1970’s, the administration had decided that the money expended defending these discharge characterizations would be better spent expanding the nuclear navy. The new policy, effective as of January 1981, was encoded as part 1, section H of DoD Instruction 1332.14, concerning administrative separations for enlisted personnel, and DoD Instruction 1332.30, concerning separations of regular officers for cause. These instructions, which any president had the authority to simply repeal by executive order, as Bill Clinton would later promise, but fear to do, constituted the “ban” that activists like me fought so hard to “lift” in the years before Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (DADT).

Thus, the Judge Advocate General (JAG) assigned to advise me was able to offer a choice that wouldn’t have been an option only seven years earlier: by voluntarily “admitting to homosexuality,” I could avoid a criminal investigation, possible criminal charges and brig time, and hope for an honorable discharge, benefits intact. I left his office unsure what to do. I had no clue how they had discovered my secret. I didn’t know what evidence the NIS officer kept hidden in the dark brown folder on his desk. When I called Lambda Legal and the Task Force, advocates there had little helpful advice as neither organization had yet fully engaged on the issue, but they agreed I should probably not risk an investigation, and that I could not trust the JAG to represent my interests if I did. They hinted that a big gay world awaited me, but otherwise could do little to help; already the queer world begged for Michelle Benecke and Dixon Osburn.

The threat of serious punishment if I resisted discharge was real, and the pressure to capitulate and “admit” was powerful. That I was nearing completion of such an elite program with so demanding a curriculum in calculus, engineering, and nuclear physics complicated my decision. I had overcome my own considerable limitations, especially a strong aversion to mathematics, in order to come this far. I didn’t want to quit, but the word “sodomy” rang in my ears for the next several days.

My suspiciously concurrent diagnosis with HIV would complicate this entire process, and lead me to speculate, years later, that perhaps a Western Blot result was the only evidence the NIS officer withheld in that dark brown folder as he declared the suspicion against me, segregating by dramatic pause the filthy word he seemed to fear capable of contaminating all other speech: sodomy. Like every good recruit, I had memorized the articles of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) during boot camp. For Article 125, prohibiting sodomy, our instructors had drilled into us a phrase they must have construed as the heart of the law: Penetration, however slight, is sufficient to complete the offense. With whom had I shared penetration, however slight, other than those similarly compelled to secrecy by Article 125? Who had reported me? Without this knowledge, determining my legal vulnerability was impossible. If I were convicted of violating Article 125, the military court could imprison me for five years.

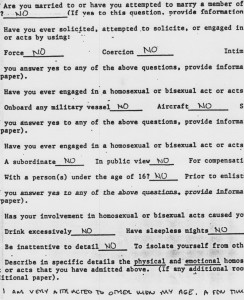

Finally, on 17 February, I reported to the yeomanry division, my pristinely white “Dixie cup” in hand, where an ironically effeminate petty officer guided me through the paperwork that would comprise my admission to homosexuality, the feeblest such confession I would ever make. Immediately upon my admission, NNPS dis-enrolled me from its coveted training program, and transferred me to temporary duty with base security where, until my administrative separation in April, I oversaw the detail of sailors who served gate watch, a responsibility I found comically telling, years later, as I contested DoD claims that “homosexuality compromises security,” a long-held justification for upholding the “ban.” On my last day of active duty, after donning civilian clothes to be escorted through the main gate by a security detail, a first class petty officer confiscated all my uniforms, every non-civilian stitch then in my possession except for a few items I’d left in Virginia over winter leave, as well as my military identification card, the indispensable tessera of military life, because, he told me, “We don’t want any faggots sneaking back on base.”

Today, I wonder if that first class petty officer is still alive, and, if so, whether he thought of me when he heard Panetta’s news. I certainly thought of him. Even now, as clearly as if before my very eyes, I can picture his hand, snatching away the plastic ID card I had placed on the desk as he ordered. Soon, instead of confiscating identification cards from queer sailors, the U.S. Navy will be issuing identification cards to queer spouses. Today, I must count that as a victory.

Today, though, I also have to wonder if congress will ever repeal Article 125 of the UCMJ. Although the 112th congress nearly repealed it in the National Defense Authorization Act, this last U.S. law criminalizing consensual sodomy between adults remains in effect, tarnishing every shining bit of progress we might celebrate. The same law once used like a cudgel to intimidate me into “admitting to homosexuality,” now consoles radical fundamentalists who resisted repeal of DADT. The same law once used to frighten recruits into sexual conformity, now indicts our careless conflation of queer conduct and queer status. How benefit queer sailors if they can tell, but they can’t penetrate, however slightly? Although some will argue that recent court decisions suggest the chain of command will limit citations of Article 125 to cases of forcible sodomy, the congress must retire the article altogether, and the sooner the better. Just as a Confederate battle flag continues to inflict harm even when used only to cheer on the Ole Miss Rebels at a football game, Article 125 will remain harmful even in desuetude, an offensive artifact of a military that not only officially hated fags, but non-procreative sex of any kind, once even using Article 125 to convict a man named Fag for receiving oral sex – from a female. Tomorrow, hundreds of new recruits will be memorizing the UCMJ, article by article, and Article 125 will yet number among them. Today, I must count that as an ongoing and regrettable defeat.