A few years ago, I was growing medical marijuana on a nine-acre farm in Northern California as part of a small patient collective. Every fall, our collective invited everyone we knew who might be available to help us harvest, trim, cure, and jar our medicine for the year. It’s a tedious process, requiring great care if one intends, as we did, for the conserved medicine to retain its full therapeutic powers until the next harvest. Once cutting has begun, the success of the project depends on completing the work in a timely manner, so extra hands were always welcome.

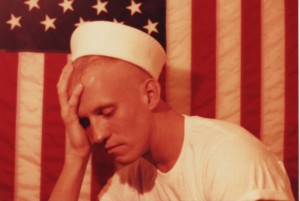

As everyone sat around the large worktable, scissors snipping furiously, meticulously trimming away any leaf matter to leave only perfect nuggets of potent flower-buds ready for their second curing, we talked about everything – music, farming, philosophy, cooking – and as these crews were usually diverse in many respects, the topics of choice often steered to the queer. So I wasn’t surprised when one worker’s mention of the recently commemorated Veteran’s Day and my partner’s interjection that I was a veteran led to a discussion of the imminent repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (DADT). But I was surprised when this femme-dyke, whom I had known for years, asserted that, because I had enlisted in the military, I couldn’t legitimately identify myself as queer. “There’s no such thing as a queer in the military,” she said.

I remembered those words when I read about Ashley Broadway. She’s the legally married spouse of Lt. Col. Heather Mack (US Army) who was denied admission to the officers’ spouses club at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. (Apparently, Mack and Broadway are queer enough by Army standards.) The controversy garnered more coverage yesterday when the Associated Press (AP) reported that the Marine Corps has advised its legal staff that spouses clubs operating on its installations must admit same-sex-gender spouses if they wish to remain on base. According to the AP, the Marine Corps commandant’s Staff Judge Advocate referred to the “stir” at Fort Bragg in his emailed instructions: “We do not want a story like this developing in our back yard.”

Interestingly, the Marine Corps’ top lawyers cite the existing non-discrimination policy applicable to such clubs, language that does not specify protection for sexual orientation. According to the AP, the emailed memo explained, “We would interpret a spouses club’s decision to exclude a same-sex spouse as sexual discrimination because the exclusion was based upon the spouse’s sex.” Perhaps that explanation will satisfy defenders of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), a law plainly intended to enforce complete non-recognition of queer military spouses, even the lawfully wedded wife of a Lieutenant Colonel.

I think my femme-dyke critic made a fair point in one logical sense: Militarism is the norm, and queerness, by definition, exists outside the norm, and therefore, “There’s no such thing as a queer in the military.” It’s also true that I didn’t self-identify as queer per se before the Navy kicked me out for being, well… per se queer. Yet, I must challenge her criticism on the larger question of the meanings of queer and queerness, especially their meanings in contrast to other terms of static identity deployed on the battlefields of identity politics.

I believe that queerness is not merely a more extreme or radical expression of non-conforming sexuality, not merely extra-gayness, or far-left anti-military and socialist gayness. Rather, queerness is the rejection of conformity as a norm. To be queer is to embrace diverse non-conformity as the only norm, to acknowledge the multi-dimensionality and fluidity of desire and sex-gender, and to cultivate a world free of the boundaries prescribed by norms of desire and sex-gender. Queerness is a reflexive idea, its all-encompassing inclusion applying even to itself, so that anyone, everyone can be queer. Queerness is an expansive, liberating idea, an idea rendered most powerful in circumstances, like military service, most dominated by norms of conformity, so that otherwise quite conventional soldiers and sailors and marines assume queer power by the most subtle of nonconforming thoughts and actions. Indeed, the military is full of queers. It always has been.

In the early years of the queer visibility movement, I lived across the street from the Marine Corps Barracks at 8th and I Streets in Southeast Washington, DC, where I earned the distinction of a place on the out-of-bounds list, local addresses marines were ordered not to visit. My experiences there corroborated my earlier suspicions, initially formulated during my active duty service, that the Marine Corps are the most homoerotic, potentially the queerest of the service branches. The corps’ subsequent, and even recent resistance to the repeal of DADT seemed to further confirm my suspicions, as the resistance itself suggested an unseen pressure, perhaps, one could say, even a latent institutional homosexuality. Of the four branches of service, the USMC has always seemed most to embody the attributes of the closet case, jarhead violence against queer neighbors once so common as to spark demonstrations like the one we staged outside my doorstep in the summer of 1990. Two decades later, the marines, at last, are peaking out of their closet, defying DOMA to queer the corps, and leading the way for the other branches of service to finally begin to acknowledge the spouses of Americans willing to die for our right to be different. And to them, my inner sailor and my inner queer can only answer: outstanding!

In the early years of the queer visibility movement, I lived across the street from the Marine Corps Barracks at 8th and I Streets in Southeast Washington, DC, where I earned the distinction of a place on the out-of-bounds list, local addresses marines were ordered not to visit. My experiences there corroborated my earlier suspicions, initially formulated during my active duty service, that the Marine Corps are the most homoerotic, potentially the queerest of the service branches. The corps’ subsequent, and even recent resistance to the repeal of DADT seemed to further confirm my suspicions, as the resistance itself suggested an unseen pressure, perhaps, one could say, even a latent institutional homosexuality. Of the four branches of service, the USMC has always seemed most to embody the attributes of the closet case, jarhead violence against queer neighbors once so common as to spark demonstrations like the one we staged outside my doorstep in the summer of 1990. Two decades later, the marines, at last, are peaking out of their closet, defying DOMA to queer the corps, and leading the way for the other branches of service to finally begin to acknowledge the spouses of Americans willing to die for our right to be different. And to them, my inner sailor and my inner queer can only answer: outstanding!